Below, we publish the statement of Jan Ciechanowski, Ambassador of Poland, dated July 5, 1945, on his resignation as a result of the withdrawal of recognition of the Constitutional Government of Poland by the United States, and a biographical note on Ambassador Jan Ciechanowski.

Polish Embassy

Washington, DC

July 5, 1945

In connection with the withdrawal of recognition of the Constitutional Government of Poland by the United States, I am forced to leave my position and I do so with deep personal regret. Before I leave, however, I feel obliged to emphasize the tragic situation in which the Polish Nation currently finds itself as a result of the world conflict, which brought victory to Poland's allies, while Poland, which was the first to fight and fully contributed to the common victory, brought defeat and loss of independence.

The fate of Poland will be better understood when we realize that even defeated Nazi Germany lost less of its territory in the war than Allied Poland was forced to give up in victory. Moreover, Poland remains under the continuous uncontrolled occupation of a foreign power, which imposes on it a government and a political, social and economic system that are alien to it. Poland's record as a belligerent member of the United Nations during that war is indisputable. Its initial armed resistance to the German aggression against Poland in September 1939 gave France and Great Britain the time necessary to prepare their defense. Later its army, navy, and air force fought in Norway, France, the Battle of Britain, Africa, Italy, Normandy, Belgium, Holland, and Germany, and its underground Home Army performed the miracle of sabotage, guerrilla warfare, and open combat against the Germans and greatly assisted the Russian armies in their advance through Poland.

During the war, Poland's efforts were appreciated by her allies, and declarations of admiration and encouragement were generously made. Poland was called the "inspiration of nations" and was repeatedly promised independence and support after the war. These words of encouragement were accepted by the Poles at face value. They believed deeply in the sincerity of the words spoken on behalf of America, which they had always trusted and admired.

How can one explain to these unwavering fighters for freedom and democracy that after the victory of the United Nations the principles they fought for will no longer apply to them? How can one explain to the Polish people that their country is merely a mobile home, to be pushed east or west, depending on the imperial aims of any of its powerful neighbors, contrary to the principle of national self-determination for which they fought? One day the answers to these questions will have to be found if justice is to survive.

Insidious propaganda has managed to convince the public that Poles are always hostile to Russia. While this propaganda has been allowed to flourish, the other side of the picture has been almost completely suppressed. The public continues to ignore the details of Russia's actions in Poland and its treatment of Poles during the war, both in Poland and in Russia.

The fact that the Soviet Government steadfastly refused to admit any Allied or neutral observers to Poland is in itself sinister. Throughout the war the Polish Government itself contributed to this deplorable obfuscation of the true facts concerning Polish-Soviet relations in the name of Allied unity as essential to common victory. Moreover, it hoped that by avoiding friction it would be easier to reach an understanding with Russia which it sincerely desired.

Public opinion too easily forgets all the attempts made by the Polish government and people to reach an understanding with Soviet Russia on normal principles and within the framework of international law. It forgets that these efforts were invariably rejected by Russia, which then blamed and blamed the Polish government for the lack of understanding, whether it was the government of General Sikorski, Mr. Mikołajczyk, or Mr. Arciszewski. Each of these truly democratic governments was accused of being composed of "fascists," "collaborators," and "reactionaries."

At any time during this war, the problems that required resolution between Poland and Soviet Russia probably could have been resolved if Russia had allowed representatives of the legal Polish Government and the Underground to sit down with her representatives and deal with these problems in an atmosphere of mutual goodwill. But Russia preferred to present them - not as Soviet-Polish controversies, but as quarrels of opposing factions of Poles among themselves. Poland, represented by its legal Government, was never allowed to participate in the discussion of Polish-Soviet relations. Examples are the conferences in Teheran and Yalta.

Decisions concerning Poland must therefore be treated by the Polish Nation as judgments "in absentia". No nation, no government truly representing its people, could ever accept decisions concerning its territory or system of government taken without its participation.

The Polish nation is deeply attached to its traditions of individual and social freedom. It will never stop fighting for these ideals. It will never sacrifice them as the price of agreement. It will never accept any system of government contrary to these principles and imposed on it by any foreign power or group of powers.

On June 29, Mr. Raczkiewicz, the constitutional President of the Republic of Poland, issued an official Declaration to the Nation from London, in the last paragraph of which he said:

... I remain in my position both in accordance with the provisions of the Constitution currently in force and, I believe, in accordance with the will of the vast majority of the Polish people. I am certain that my decision will be understood throughout the world by all who value freedom, justice and law more than brutal force or the momentary victory of violence. It will be the duty of the citizens of the Republic of Poland, suffering so painfully under many blows, to ensure that the great traditions of our national culture are not lost; it will be their duty to maintain fidelity to the legitimate authorities of the Republic of Poland and not to weaken in their striving to restore the Republic of Poland to its rights and its independent place among the free nations of the world. We live in a period of great dangers and difficulties for our nation and our state, but I deeply believe that Almighty God will bless our efforts and ensure that Poland emerges from this new trial victorious, safe and with its rights intact.

As the Ambassador of Poland and the personal envoy of the President of Poland, when leaving the post of Ambassador to the United States, I will be guided in my actions solely by the directives issued to all Poles by the constitutional Head of State of Poland.

Translated by Marek Maciołowski into Polish from the English original contained in the book "Defeat In Victory" by Jan Ciechanowski, Polish Ambassador to the United States during the war years; pp. 412-415 London, Victor Gollancz LTD, 1948..

Jan Maria Włodzimierz Ciechanowski was born on May 15, 1887 in Grodziec, Kingdom of Poland, Russian Empire (now part of Będzin, Poland). He was the son of Stanisław Ciechanowski (1845–1927) and Maria Garbińska (1863–1953), and the older brother of Stanisław Ciechanowski (1913–1992). He came from a minor noble family, the Ciechanowskis, who were of Jewish descent. His father was an entrepreneur and owner of several mines and factories in Grodziec. From 1911 to 1917, Jan Ciechanowski was the administrative manager of his father's operations.

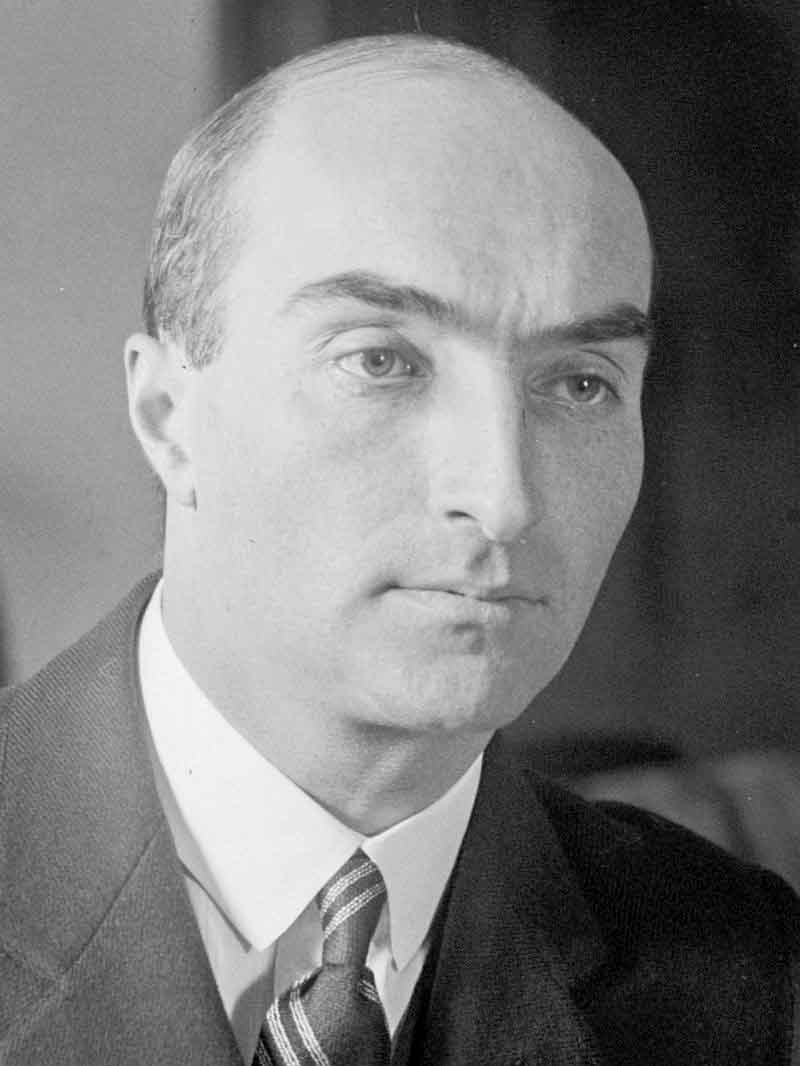

Jan Ciechanowski in 1925 (Source: Wikipedia)

In the years 1919-1925 he was a parliamentary counselor at the Polish embassy in London. From 12 October 1925 to 20 February 1929 he was a Polish ambassador to the United States. In 1928 he signed with Frank B. Kellogg, the US Secretary of State, treaties on reconciliation and international arbitration between Poland and the United States.

In 1939-1940, during World War II, he was Secretary General of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the Republic of Poland. From 16 December 1940 to 5 July 1945, he was the Polish ambassador (Polish government in exile) to the United States. On 1 January 1942, he signed the Declaration by the United Nations as a representative of Poland. From 1 November to 7 December 1944, he led the Polish delegation to the International Civil Aviation Organization congress in Chicago, Illinois, USA, which led to the signing of the Convention on International Civil Aviation on 7 December 1944.

After World War II and the end of his ambassadorial service, he decided to remain permanently in the United States. He became a member of the Polish Independence League, a political party and organization founded in 1944 that advocated for Polish independence from external powers, primarily the Soviet Union.

Ciechanowski died on April 16, 1973 in Washington, D.C.