He was one of the most talented strategists of the twentieth century among the advisers to the presidents of the United States. He went down in history as a citizen of the world, mitigating conflicts, and at the same time perfectly understanding the threats related to the policy of the Soviet Union. From our point of view, however, the most important thing is that being a world politician, he never lost the Eastern European sensitivity inherited from his first homeland — Poland. Significantly, especially today, he was one of the first politicians to pay attention to the role of organizing Polish-Ukrainian relations after 1991. I am talking about Zbigniew Brzeziński, an outstanding Soviet and political scientist and security adviser to President Jimmy Carter.

Zbigniew Brzeziński during a speech in Oslo in 2016. Photo: Terje bendiksby / NTB scanpix / TT newsagency / Forum (Source: dlapolonii.pl)

He was born on March 28, 1928 in Warsaw in the family of diplomat Tadeusz Brzeziński. This origin and social position will shape his future thinking not only about Poland, but will also direct his attention to global problems. Due to his parents moving, Zbigniew lived in France, and then, until 1935, in Germany. In 1938, Tadeusz became the consul general of the Second Polish Republic in Montreal, and the family moved to Canada. In 1945, Zbigniew studied economics and political science here, which he continued at the Russian Research Center at Harvard University. After defending his doctorate, he was employed at this prestigious university.

In 1959, he became a professor at Columbia University. Soon he became the director of the Institute for Research on Communism established there.

The beginning of his political path was working in the Office of Political Planning of the State Department, where he was responsible for US policy towards Eastern Europe. Later, among others, he served as chairman of the Trilateral Commission between the US, Japan and European countries. While on the commission, he met then-governor of Georgia Jimmy Carter and became his foreign policy adviser.

The turning point in Brzeziński's career was January 1977, when he was appointed security advisor to the 39th president of the United States.

As an advisor, he was one of the main authors of the groundbreaking meeting at Camp David, during which an unprecedented agreement was reached between the Israeli and Egyptian authorities ending the Yom Kippur War. He also played a significant role in the disarmament negotiations between the United States and the USSR, which went down in history as the Strategic Arms Limitation Treaty II (START II).

President Jimmy Carter and Soviet General Secretary Leonid Brezhnev sign the Strategic Arms Limitation Talks (SALT II) treaty, June 18, 1979, in Vienna (Austria). Brzezinski is directly behind President Carter. (Źródło: Wikipedia)

What is most important from our point of view, however, is his involvement in Polish affairs, i.e. supporting "Solidarity" and taking into account Polish threads in American strategic thinking. His activity as an advisor to the president coincided with the gradual reorientation of American policy towards the Soviet empire from conciliatory to confrontational. This is probably why the Democrats, who were fixated on the era of detente, considered Brzeziński a hawk, and the Republicans of the 1980s – a dove. His position cannot be assessed unequivocally. He was a child of his era – dominated by the Cold War conflict – but he was able to significantly anticipate it. Therefore, some of his concepts remain surprisingly valid.

First of all, it should be remembered that Zbigniew Brzeziński is not only a politician, but also — and perhaps above all — a political scientist whose work strongly marked the conceptualization of American geopolitics in the second half of the 20th century. He is known as a theorist of totalitarianism who sees the twin nature of Nazism and Communism . One of his ideas, described within the broader concept of international relations as a large chessboard, was to mark several countries on the world map as so-called pivots. To put it very simply, such pivots were to play a key role in the regional balance of international forces.

Ukraine was one of them, to Brzeziński. It's hard not to see how prophetic that thought turned out to be. What exactly is it about? According to Carter's adviser, Ukraine balances relations between the "Center" (where Russia is rather the most important) and the West (today: the European Union and, indirectly, the USA). So if Moscow wants to become a world power, it must control Ukraine. Without it, it remains only an Asian regional power of the "worse sort". The aggression of the Russian Federation against Ukraine, which began in February 2022, clearly showed that Vladimir Putin is Brzeziński's "dutiful student" and fits perfectly into this way of thinking. Putin understands that controlling Ukraine will allow him to relate to the imperial position of the USSR.

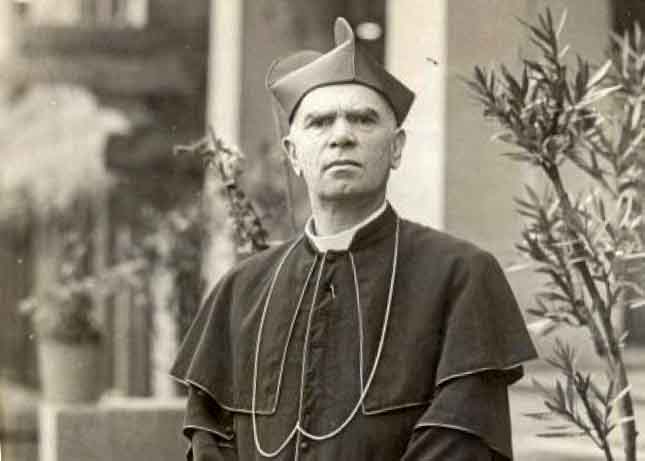

Zbigniew Brzezinski in 1977. (Source: Wikipedia)

Brzeziński's timeliness is manifested in one more thread related to the Soviet system. E.g., he drew attention to its irreformability. This went against the current of most American political theorists and practitioners, who hoped that either confrontation or conciliation would bring about fundamental changes in the system. This was how Brzeziński perceived the perestroika reforms initiated by Mikhail Gorbachev in the second half of the 1980s, perceiving in them mainly in terms of the potential for decomposition, not development. Also, at the beginning of the 21st century, when commenting on Vladimir Putin taking over the helm of the Kremlin, he did not see in him the potential of a reformer, although he was optimistic about the possibility of "infecting" ordinary Russians with the Western mentality.

The latter leads to the conclusion that Brzeziński was not infallible. The Russian aggression against Ukraine in 2022 and the attitude of the majority of Russian society show that the belief in the convincing power of the Western worldview is largely a pipe dream. The imperial mentality of the Genghis Khan hordes remain at least as “attractive” to the Russians.

In the 1970s, the administration of Jimmy Carter, inspired by Brzeziński, began to use the universal language of human rights to try to weaken the Eastern Bloc ideologically. It was a smart and legitimate move, taking advantage of the fact that Moscow and its satellites signed the Final Act of the Conference on Security and Cooperation in Europe in 1975, in which they pledged to respect these rights.

The reality of the 21st century has shown that the indications by the West and international organizations of cases of violation of the principles of democracy, civil liberties and the rule of law had practically no impact on the gradual reconstruction of the dictatorial system of power in the Russian Federation. These pressures did not stop Putin’s aggressive moves either: from the attack on Georgia in 2008, through the annexation of Crimea in 2014, to the aggression against Ukraine in 2022. Attempts to “Occidentalize” Russia, tying it with an increasingly dense network of trade agreements and playing the human rights card — and all these elements can be found in Brzeziński's old ideas about the USSR — turned out to be unsuccessful. As part of a certain intellectual school, they could even be called the second appeasement. Of course, Carter's advisor himself is not responsible for this.

Brzezinski hosts a dinner for Chinese Communist leader Deng Xiaoping in 1979 (Source: Wikipedia)

Wishing to weaken the Soviet empire, Brzeziński also followed the way of thinking of his predecessors (Henry Kissinger and Brent Scowcroft) focused on building relations with communist China. Of course, the status of Taiwan remained a bone of contention, but Washington came to the conclusion that building bridges with Beijing could effectively weaken Moscow. In the balance of power at the time, this strategy turned out to be effective. However, it had one serious, long-term effect: the gradual, slow but steady strengthening of China's importance on the international stage, both politically and economically.

And that is what creates today, in 2022, a completely different situation. Joe Biden, unlike Richard Nixon, Gerard Ford, or Jimmy Carter, sees the confrontation with Moscow as bundled with the conflict with Beijing. There is no room here to judge the validity of this strategy. It seems that the United States, wanting to continue to play the role of the world's policeman, cannot act otherwise. It is significant that the attitude of the Biden administration went in a different direction than Brzezinski's concepts.

However, one thing has not changed: both during the Cold War and today, the aggravation of the conflict between the West and Russia, and as a result the weakening of the latter, always implies the strengthening of China's position. Brzezinski, had he lived, would have noticed it.