In the wake of Copernicus's publication, Martin Luther declared, 'This fool wants to turn the whole science of astronomy upside down.' He was joined by the renowned contemporary scholar Philip Melanchthon (1497-1560), revered as the ‘prince of science,’ echoed this sentiment, labelling the Polish astronomer's theory as ‘absurd’ and urging its outright rejection, arguing that ‘wise rulers should restrain [Copernicus's] talented recklessness.’ Galileo Galilei's correspondence with Johannes Kepler in 1597 sheds light on the challenges faced by proponents of heliocentrism. He reports that ‘for many years he has been working in the spirit of this theory, but he cannot dare to advertise his arguments for fear of the fate of Copernicus, who, although he gained immortal fame among some, unfortunately, he was ridiculed and condemned by countless others (for that is how many fools there are).' Consequently, even a renowned and universally respected scientist such as Galileo faced derision for discussing a concept that is now widely accepted.

Galileo (1564-1642), the author of ‘Dialogue Concerning the Two Chief World Systems, Ptolemaic and Copernican’ (1632), struggled against scepticism even from academics at the Sapienza University of Rome. For many years, the Copernican theory was notably absent from university curricula. It wasn't until Isaac Newton's groundbreaking work on gravity and other scientific advancements built upon the foundations laid by Johannes Kepler (1571-1630) and Galileo (1564-1642) that the heliocentric model began to gain traction in educational institutions.

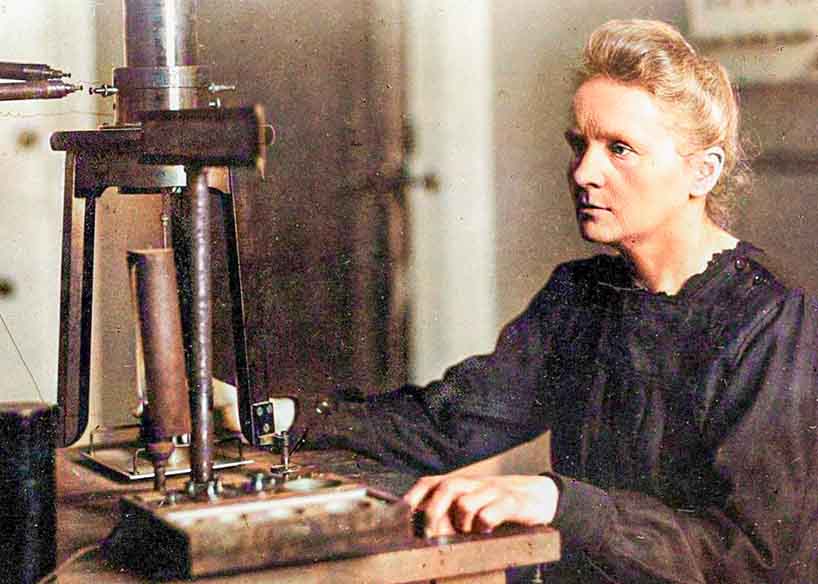

Copernican exhibition in Rome (Source: DlaPolonii.pl)

Reflecting on the prolonged neglect of Copernicus's theories in ‘De revolutionibus’, Italian scholars sought to rectify this oversight, especially as they considered Copernicus's own academic journey. After studying at the Krakow Academy, he furthered his education in mathematics, astronomy, medicine, and law for 7 years at various Italian universities, including Bologna, Padua, and Ferrara, where he earned a doctorate in canon law in 1503. In ‘On Revolutions’, Copernicus recounts observing a lunar eclipse in Rome three years earlier, during the Holy Year on 6 November, which further solidified his ties to the city.

The Jan Retyk's work from 1540 was also remembered with the words: ‘When the doctor and my teacher in Bologna, not so much a student as rather an assistant and witness of the observations of the outstanding scientist Domenico Maria [Novara], and in Rome, around 1500, at around the age of 27, among a large crowd of students and in the company of distinguished men and experts in this field of science, as Professor of Astronomy (Mathematum), he finally recorded his observations here in Warmia, living off his studies with the utmost care.' Pierre Gassendi agrees, writing, ‘When he later arrived in Rome, he was soon considered to be only slightly less than [the famous astronomer] Regiomontanus himself. Therefore, he was made professor of Astronomy (Mathematum) to great acclaim. He [i.e. Rheticus] lectured to a large crowd of students and in front of a group of distinguished men and experts in this field of science.’

During this significant period, just before the 400th anniversary of the birth of the astronomer in 1873, Jan Matejko began his ambitious project, the painting titled 'Astronomer Copernicus, or Conversation with God'. In parallel, fellow artist Wojciech Gerson envisioned a similarly grand work, 'Lecture of Copernicus in Rome', inspired by pivotal texts related to Copernicus's groundbreaking theories.

The desire to honour this brilliant astronomer also emerged in the Eternal City. In 1872, Domenico Berti, a professor of the history of philosophy at the University of Rome and a former minister of education, along with Filippo Serafini, rector of the same university, proposed the establishment of a dedicated Copernicus museum in Rome.

This initiative aimed to commemorate the 400th anniversary of the author of 'On the Revolutions of the Celestial Spheres'. As a result, a series of commemorative events were organized on 19 February 1873 at the universities of Bologna and Padua, which included the publication of numerous works in Italy focusing on Copernicus and his followers, particularly Galileo.

Among the various artistic tributes to Copernicus, the painting that captured the most attention was created by Alexander Lesser, titled 'Copernicus on his Deathbed'. In this poignant portrayal, the ailing astronomer is depicted surrounded by friends, holding a copy of his monumental work 'De revolutionibus' in his hand. The ideas reflected in this artwork likely began to take shape during Copernicus's studies in Krakow and Italy. In March 1514, Maciej of Miechów, a professor at the Academy of Krakow, noted the existence of 'Comentariolus', or 'Small Commentary', which famously stated, 'All spheres revolve around the Sun'; thus marking the dawn of a new era in the history of science.