From the moment Adolf Hitler came to power in 1933, Europe embarked on a path from which it could never turn back. At least until 1938, the Third Reich could be contained because it did not yet possess the power that brought the lion's share of the continent to its knees in 1939-1940. However, that was not done.

The decisive factor was a mechanism as old as geopolitics itself – war cannot be waged without will. In the realities of 1930s Europe, this will of the rulers and society to wage war was lacking primarily among the English and French, who were struggling with the trauma of World War I. However, it was not lacking in German society, led by a man who practically exuded this will, invoking revisionist and superpower slogans.

Will alone, though essential, is not enough to ignite a world war. This requires money, weaponry, technology, population, resources, a system of alliances, and a plan of action that determine victory or defeat. In these respects, no one in Europe—including Germany—was prepared for a conflict of this scale in the 1930s. However, Hitler consistently sought to change this state of affairs. He encountered no resistance along the way.

England and France, although initially much more powerful than Germany, were grappling with internal economic and social crises. Moreover, they were gripped by the desire to avoid another war. Therefore, when Hitler violated the Treaty of Versailles in 1936 and remilitarized the Rhineland, there was no response from the major powers. In 1938, he annexed Austria and, with the consent of England and France, occupied part of Czechoslovakia. In March 1939, he completed the task and incorporated Bohemia, Moravia, and Cieszyn Silesia into the Reich. Poland was next on the list.

German Heinkel He-111 bombing Warsaw in September 1939 (Source: Wikipedia)

Only then did the West understand that the pursuit of peace at all costs had, in practice, paved the way for another world war. England and France were undoubtedly not ready for war, which largely explains their reticence, but Germany was in no better position until 1938-1939. The Western powers overestimated their capabilities and blindly believed that Hitler—like their own elites—would not risk starting another world war, contenting themselves with restoring the Reich's great power status. Poland itself had no influence on this. Warsaw's diplomacy was not perfect, and many mistakes were made in this area during the interwar period, but even the best strategists in history, managing Polish policy, would not have been able to reverse the course of events. Hitler could only be stopped by working together with England and France. Their will was lacking.

A potential alliance with the USSR against the Third Reich was out of the question. Letting the Red Army onto Polish territory would be tantamount to surrendering Poland's newly regained independence without a fight. Allying with Hitler was also irrational. In the event of a joint attack on the USSR with Germany, the Poles had to consider war with the Anglo-French-Russian coalition. In 1939, it was not assumed that France would quickly collapse under German pressure, so the prospect of competing alongside Hitler on two fronts against such a powerful bloc was unattractive. There was also no reason to believe Hitler that after the USSR's eventual defeat, Poland would not be completely subjugated to the Reich, leaving it without room for maneuver or allies to rescue it from German rule. Even if Germany ultimately lost the war to the coalition led by the US and Great Britain, Poland's fate would depend on the victors. The victors, in turn, would treat it as a defeated vassal of the Third Reich, with whom they could do anything.

If, however, Hitler had allied himself with Poland and struck west first, the Second Polish Republic would have become a buffer between Germany and the USSR. Stalin's reaction would then have had to be considered, as he would likely have attacked Poland, taking advantage of Hitler's involvement in the West. The prospect was a solitary fight against the USSR, while Germany was tied down in France and there was no guarantee of victory.

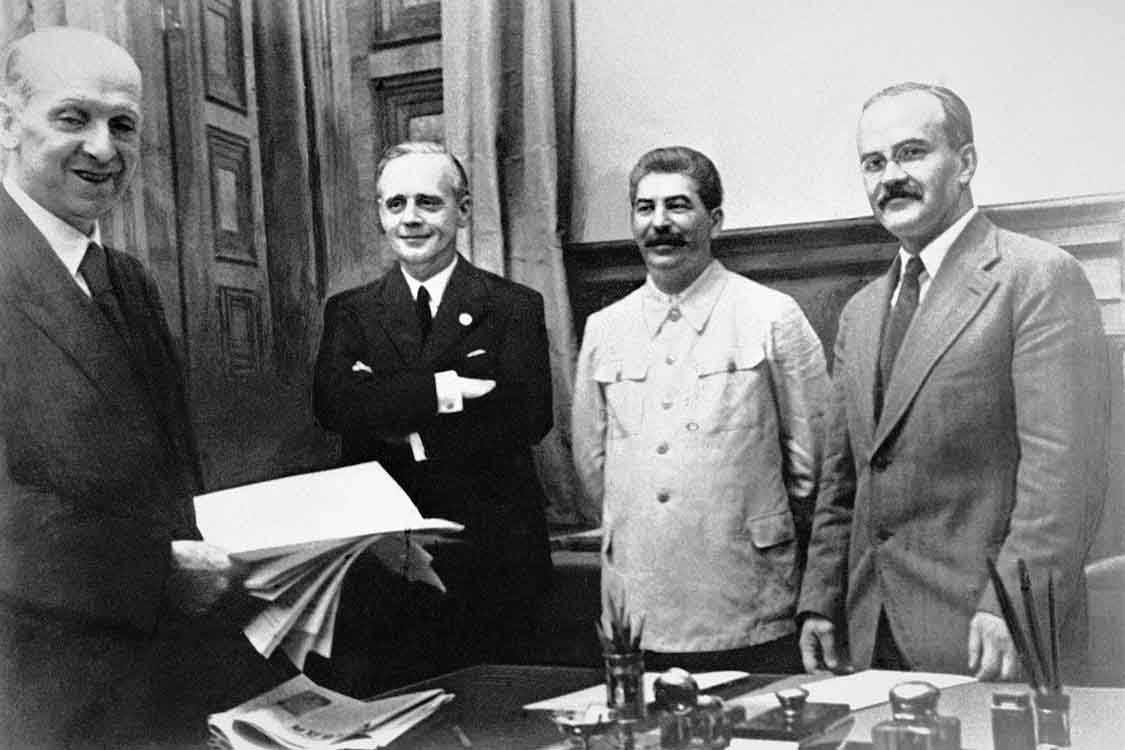

The Poles chose the most logical option: an alliance with the Franco-British coalition, which assumed the Third Reich's first attack and then a joint fight against Hitler with the support of the two empires. Their guarantees were also uncertain, but still stronger than those of Hitler or the Soviets. The secret protocol attached to the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact and the resulting cooperation between Germany and the USSR were unknown in Poland at the time. However, even if this had been widely known, Poland had only poor alternatives to choose from. A scenario in which both Germany and the Soviets lost World War II, with Poland benefiting from their defeat and respected by the victors of the conflict, was impossible.

In this context, the final outcome of World War II, in which Poland lost its independence to the USSR but retained its separate identity and borders with the Western lands, appears as a brutal and tragic, yet nonetheless not-so-bad, conclusion to this historical epic. It's hard to imagine a more favorable scenario that could have been realistic. However, even worse scenarios could easily have been envisioned.