On May 18, 1944, at dawn, the world heard the news, which — as Polish patriotic commentary — was accompanied by the song "Red Poppies at Monte Cassino". The author of the words was Feliks Konarski "Ref-Ren" — a poet and soldier of the 2nd Corps of General Władysław Anders — and the composer of music was Alfred Schütz — a conductor and member of the Polish Soldier Theater stationed in Compobasso, near Monte Cassino.

This article was written mainly on the basis of the memories of a participant in the Battle of Monte Cassino, Maj. Leonard Jędrzejczak, a Bydgoszcz citizen living in Milwaukee, returning to those events, to those days of glory and blood, to the smell of red poppies, to history.

Major Leonard Jędrzejczak (Photo: Marcin Murawski)

1943 was a turning point for the Second World War. In the east, the Germans were stopped at the foot of the Caucasus, and their defeat at Stalingrad in February 1943 marked the end of their successes. In North Africa, Axis forces were forced out of Egypt, Cyrenaica, and Tripolitania. In May 1943, on the African front, all enemy resistance ceased. In Italy, Mussolini was overthrown, and the new government of Prime Minister Marshal Pietro Badoglio began talks with the Allies. On September 3, Italy signed the capitulation. The Allies, who had already landed in Sicily, began marching north.

The German command was not surprised by this turn of events. As early as May 1943, it drew reinforcements and prepared appropriate plans in the event of the Italians withdrawing from the war. Using the natural relief of the Apennine Peninsula, the area was appropriately fortified with a series of lines of defense. The main one was the Gustav Line. It ran over the Tyrrhenian Sea along the Garigliano and Rapido rivers, through the high Apennine range to the town of Alfedena and further along the Sangro river bank on the Majella Massif to the Adriatic Sea.

Map of Italy with Monte Cassino marked (Source: Wikipedia)

The length of this line, crossing the Apennine Peninsula from sea to sea, was about 140 km (87 miles). Three more stood in front of the main Gustav Line: Victor, Barbara, and Bernhardt. It took three months to overcome these obstacles. Before the Allied forces faced the Gustav Line, the Germans had drawn the best troops and excellent weapons from the African front, which was no longer active, and from France. The terrain and the season of the year worked in their favor. The autumn downpours and the vast, swampy terrain made it impossible for heavy vehicles and artillery to advance. The Germans had a decisive advantage in this area and controlled the actions of the allied forces.

Parallel to the frontline fights, a diplomatic battle was fought. The Allies worked out their plans, and the Soviets put in place conditions that forced the plans to change. An example of such an operation was the abandonment of cooperation with General D. Mikhailovich and helping the partisans of Josip Broz Tito. Already at the Tehran conference, the basic plan for the political division of influence in Europe was outlined, and military strategies were adapted to this plan.

The Polish II Corps was ready to fight. The Poles wanted to fight to prove the slander of Soviet propaganda wrong. On November 14, the commander-in-chief, Gen. Kazimierz Sosnkowski, personally visited the army. In his speech, he clearly expressed what goals and values the war is about and what tasks Poland is facing. Among other things, he said:

Today, when we find ourselves under the fire of unfavorable to us propaganda, our refuge is a clear conscience and the conviction that no honest and just person can accuse Poland of anything. The Poles, however, do not want to accept the prospect of partitioning one of the Allies in favor of the other at any cost. Our nation (...) cannot find itself in a situation where the rights of Poland would be diminished on the day of victory. (...) Fortunately, we have the legitimate government of the Republic of Poland and legal state authorities. Their existence makes us soldiers of the Polish Republic, not a mercenary army serving someone else's raison d'état.

After this visit, preparations for the deployment to Italy began. They were returning to Europe, and from here it was close, ever closer, to Poland. On December 21, 1943, they arrived in Italy, in the port of Taranto.

After Christmas, the II Corps began to move closer to the front line in transports. They were to replace the British troops exhausted from trying to break through the enemy's defense lines. The weather conditions for the soldiers who came from the hot climate were difficult, but worse than the blows of nature, cold and disease, were the wounds inflicted by those who were considered friends.

Huge portraits of Churchill and Stalin hang in the background, concress for aid to Soviet Russia, Brisbane, Australia, 1941. The slogan says: "British-Russian unity against Nazism" (Source: Wikipedia)

On February 22, 1944, the Prime Minister of Great Britain, Winston Churchill, gave a powerful political speech in the House of Commons, in which the issue of Poland was of utmost importance. In it, he said, among other things:

The fate of the Polish nation is at the fore in the thoughts and policies of the British government and parliament. I was pleased to hear from Marshal Stalin that he, too, considers it necessary to create and maintain a strong and independent Poland as one of the leading powers in Europe. (...) We have never guaranteed any Polish border. We did not agree to the occupation of Vilnius by Poland in 1920. British views in 1919 found expression in the so-called Curzon Line (...). I feel deep sympathy for Poles, but I also have understanding for Russia's position. The liberation of Poland can now be achieved by the Russian armies, having sacrificed millions of lives in breaking German military power. I do not have the impression that Russia's demands to secure its western borders go beyond what is reasonable and just.

"Reasonable and just" demands from Russia meant the annexation of almost half of Poland's territory before 1939 and the loss of 1/3 of its population. At first, the Polish army was in turmoil and then bitterness set in. Churchill's authority, whom they considered a friend of Poland, weakened greatly, but the soldiers believed that there would be no free Poland without defeating fascist Germany. Overcoming bitterness and grief, they will fight honorably to the end. Never before have honor and homeland meant so much to a Polish soldier residing in the trenches, on any section of the front.

The commander-in-chief on the Italian front, General Alexander, planned another attack on the German positions to move north. On the way to Rome, however, Monte Cassino stood — a rocky, steep mountain massif, emerging from the Rapido valley and the Liri River, giving rise to a relative height difference of over 500 m (1,640 feet), and at the highest point — Monte Cairo — 1,669 m (5,476 ft). This massif is 4 km (2.5 mile) and, in some places, 6 km (3.7 mile) wide and about 8 km (5 mile) long. This was the only possible road from the south of Italy to Rome.

Monte Cassino, according to the Roman historian Titus Livius, became a Roman colony in the 4th century BC. It has always been a gate that opens the way from the south to the Eternal City — Rome. It has been a stronghold since the wars with the Hannibal's army.

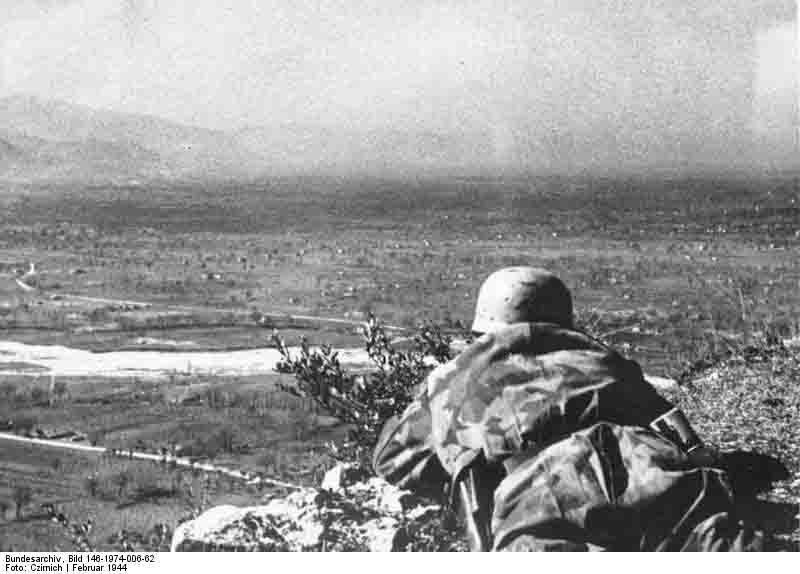

During World War II, this hill was an advanced stronghold in German defensive positions. The Germans duly used the natural defensive qualities of the area and, with the latest means of military technology and their experience, greatly enhanced its defensive potential. The basis of the defense was a strong fire system — weapons that fired both high-speed and flat-track missiles — and their great flexibility, allowing one to focus fire anywhere. In the depths of the German positions, this fortified massif at the foot of Monte Cairo was connected to a second defensive line, known as the Hitler or Senger Line. The town of Piedimonte, built entirely of stone, dominates the Liri Valley that runs almost at its feet and along the main road of this valley, Via Caselina. The Germans turned it into a fortress, by strengthening each building and erecting additional concrete shelters for cannons and machine guns. Just like Roman historians, German strategists called Monte Cassino "the posts of the gate to Rome." The crew of its defenders were especially chosen army units. These were almost one hundred percent volunteers, selected on the basis of physique, morality, and all well-trained.

German snipers had excellent oversight in the area (Source: Budersarchiv/Wikipedia)

All this confirmed the opinion that this place was really impossible to take. This was demonstrated every day in 1944 when British, American, French, Indian, and New Zealand troops persistently attacked these rocky hills. Unfortunately, without success. On February 15, US bombing turned the monastery into a pile of rubble. The Germans took advantage of this and placed machine gun nests on the rubble, which pinned the attackers to the ground.

In April 1944, the command of the allies asked the 2nd Polish Corps under the command of General Władysław Anders for support in the fighting. It seemed an impossible task for the lean forces of the Corps. However, it was a matter of honor for the Poles and for the commander. They wanted to fight to show the world that they were not afraid, that the opinion of bad Soviet propaganda claiming they had refused to fight alongside the Red Army, was false. General Anders, with a heavy heart, agreed to send the Corps up the hill.

The preparations of the troops to enter the action began on April 4. The commander performed aerial reconnaissance of the entire section that the Corps was about to attack. Then a map study followed, aerial photography, and terrain exploration that had to be done only at night and very often consisted of finding a way, or a piece of ground under a rock, in which to dig a hole and mask one's position. Large amounts of ammunition, food, water and all equipment needed for life and combat had to be transported, moved and hidden in the field throughout the entire depth of the area from which the Corps was to conduct operations. The transport of supplies was extremely difficult, because in the front zone there existed only two mountain roads, barely adapted to traffic, and they were under the enemy's eye and fire.

Leonard Jędrzejczak and his team moved tons of materials and equipment themselves, and their shirts never dried from sweat. He remembered the preparation time this way:

I was one of 300 radio operators divided into small groups of 3-4 people. The task of our tiny group of four was to maintain communication between the platoon (about 60 soldiers) and the command. Radio communication was more reliable because it was wireless. Telephone people were often unable to bury cables in rocky ground, so connections were easily damaged. The radio stations were heavy. Each of us brought two transmitters, batteries, and personal equipment. Together, everything weighed about forty kilograms (88 lbs). It was a tremendous physical exertion. We did everything at night and without using any lights.

Polish soldiers carry ammunition to the front lines just before conquering the abbey (Source: Wikipedia)

In order to extend the night and darken the moonlight, the entire Rapido river valley was filled with smoke. When everything was reasonably prepared, the fourth attack began, in which Poles played a significant role. The attack began on May 11 at 23.00.

General Anders, in his memoirs Without the Final Chapter, recalls the battle as follows:

Total darkness of the night and smoke. You can't see anything save a few steps. Even soldiers of the same team in a march, or in an attempt to march forward, falling in fire and jumping up again, after close explosions, or among them, lose communication, find themselves with difficulty, do not assess their ranks. From the very beginning fall the killed or wounded commanders of battalions, companies, platoons and the command is taken over by deputies and deputies-of-deputies.

Undoubtedly, this battle forms a whole, but no one can see it. And in these peculiar conditions, everyone sees even less than usual, even by today's battle standards, because he cannot see through even the closest darkness, which forms his main, however uncertain, cover. This, however, general whole is made up of a multitude of experiences of divisions, sub-divisions, and indeed! even individual people, not just military units, but human units. It is a swarm of minor epics. Some of them were suddenly killed on the spot while running forward, or falling to the ground in an explosion, taking the secret of the tomb with them. Some, shocking impressions no longer from hour to hour, but minute-by-minute, have become scraps of memories of this battle in thousands of soldiers' hearts. Only from them the epic of the whole emerges. This march up the Hill 593, onto Gordziel and Widmo, is one strand of will, bravery, effort and sacrifice, all called heroism. The fate of each soldier is one episode of this epic of heroism, all the more valuable as few will add their own pages to it.

Here is one of these pages, recorded in the memory of a participant in the battle, today a retired major, liaison officer of the Carpathian Brigade and the 2nd Corps — Leonard Jędrzejczak:

I walked with the Corps and, day after day, I was getting closer to Hell, because if there was any Hell, it was there. Preparations for the attack began on May 4, when we were to change the tired and unsuccessfully fighting British soldiers. We climbed to the designated positions at night and spent our days in the trenches. They were strange trenches. It was necessary to find some angle under the rock, dig a hole, as far as possible, using special bags, perhaps similar to those used today to build levees, put stones into them and make a hiding place, a shooting, and communication post out of it. When there was silence, we tried to listen to some radio programs. The subversive radio station "Wanda" spoke to the soldiers in Polish, persuaded us to stop fighting, promised various things. We cursed and turned off the nuisance, but boredom was what remained, because you had to sit in that trench or in some bunker during the day and wait for the equipment to be moved to a new place at night. The Germans patrolled the area all day and systematically shot at us. Whoever as much as stuck his head out of the trench, became a victim of a sharpshooter, or was hit by a shrapnel.

Finally, May 11, 11 PM came. It was my rest time. I was asleep then. A great bang woke me up. It was exactly like this poem:

The roar of the cannons opened the frightened silence

The darkness burst open by fire

Burst at the command of a thousand throats

The all-consuming fire was rising to the top

Biting and twitching reached against the sky,

It grew, and the darkness burst forth with a violent blur

It ascended the mountains from there, poured out like a flood

Showing broken trees in the passing

Among the positions hidden at the base

With us waiting for the team's sign...

(Józef Żywina - Manuscript from the front line)Artillery preparation was beginning. Over 2,000 guns pounded on all sides. We didn't know which missile would hit us, enemy's or ours. It was as bright as day. You could read a newspaper. Everything was shaking, stones were flying from all sides. It took an hour and a half, but it felt like forever to me. The gun barrels were hot. The artillery men kept them cool by dipping burlap sacks in the drinking water.

Radio stations were broadcasting encrypted messages all the time.

At 2.00 a.m. began the assault. The fight was over every inch of rock, almost with bayonets. A lot of officers and commanders were killed. After all day of fighting, we retreated to the starting positions. I had to keep an eye on the radio station, because some friends were killed and many were injured. I saw sanitary units picking up the fallen. Some bodies had been torn to shreds and it was impossible to establish their identity. Such were classified as missing. The following days were not idle either. We knew there would be another attack. We were hungry, thirsty and we had not taken off our uniforms for several days. With the radio station, I had to move to different places in order to maintain communication between the command and the artillery. During the break between May 12 and 17, that is, between the successive attacks, there was a lot of work. We in communications had to repair the equipment.

The Doctor's House was the central point of communication. I was there a lot. To this day, I remember one incident. A short hour has carved a mark on my brain and my psyche forever. I was very tired then. I haven't slept for two days. I sat down against the wall of the shelter and thought I was dreaming. Saw a strange scene. The beam in front of me felt as if it was starting to move. I figured I was hallucinating, or at least delusional. I closed my eyes for a moment, but the phenomenon did not disappear. From time to time something seemed to hit the ground. I switched on the flashlight for a moment and to my horror I saw that the beam was stuck with rats. Some of them were so down that they could not stay on it and fell. Despite the heavy fire, I got out of the shelter so as not to look at these monsters, and maybe also out of fear that they would eat me alive.

My equipment, apart from radio equipment, also included a bag with sanitary materials. We dressed ourselves for smaller wounds that did not require a surgeon's intervention. It was the second half of May, it was warm and there were plenty of red poppies blooming on the slopes of the mountains. We didn't look at them then as romantically as in the song with the words of Feliks Konarski. We used the bandages to make protective face masks, and we put poppy seed petals between the bandages. In this way, we were able to overcome the stench of decaying bodies of fallen soldiers and slaughtered mules. The stench was becoming the second enemy. It was impossible to eat, and the vomiting made it worse.

We knew there would be another assault and we were very afraid. We were in our twenties and we wanted to live so much! Sometimes we saw with the naked eye how the Germans went with the canteens for breakfast. We heard them arguing and assumed they were tired too. I felt this battle was like a boxing ring where whoever survived one more round, one more punch, one would win.

On May 17, another assault took place. From the bunker I have watched many times the rubble of the bombed Benedictine monastery. I saw a protruding fragment of the wall behind which a machine gun or some cannon hidden in the bunker was always pounding. I was transmitting encrypted reports all the time. On May 18 in the morning the shots seemed to have stopped. After 10.00 am I looked at the ruins of the monastery and saw on its broken corner, first the pennant of the 12th Podolia Lancers Regiment, and then the Polish flag. Eventually, after about an hour, the British flag was hung a little lower.

The Germans left the monastery, leaving only the wounded and the dead. However, it was not the end of the fighting, but after eight days we went to rest. Everyone congratulated us, shouted at us, but I didn't hear it. I was just thinking about going to sleep. Reflections came later.

Polish flag waving over the ruins of the monastery in Monte Cassino (Source: Wikipedia)

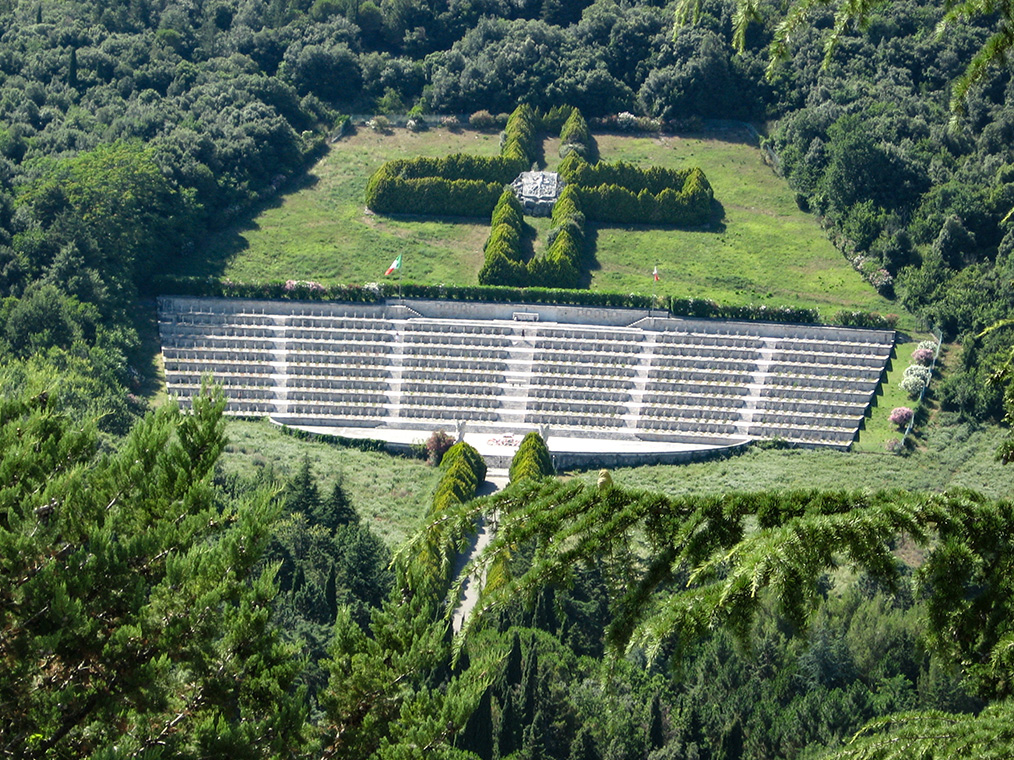

The German fortress fell, the road to Rome was open. On June 4, allied troops entered the oldest capital of Europe. They paraded in the Eternal City without us. We, Poles, were burying the dead after a hard battle. They all found eternal rest in the cemetery at the foot of hill 593, for which they had fought their hardest battle. 1072 soldiers' graves decorated with white crosses were built there.

We returned to the battle site after three weeks. The poppies were still blooming, and you could still smell the nauseating smell of blood. Each of us thought silently: 'I'm still alive'...

The next time I was at Monte Cassino was with my wife, in 1984. Then we were happy to visit our Pope, John Paul II. With him, as with General Anders twenty years earlier, we now had our hopes, not so much for the return to Poland, because everyone had somehow arranged their lives in exile, but for the freedom of Poland.

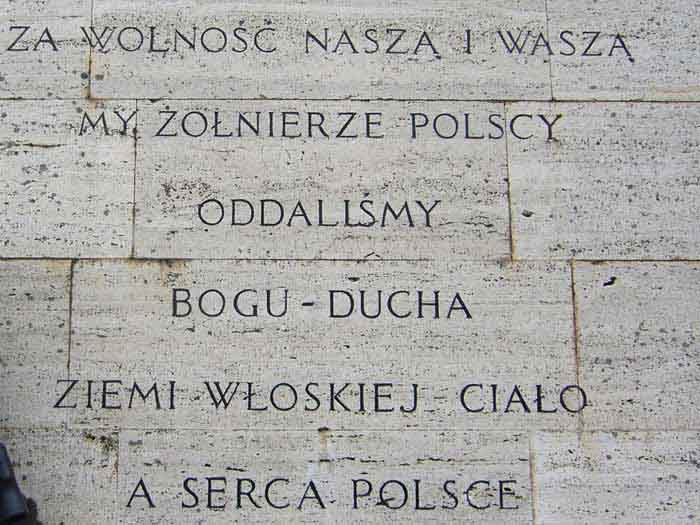

The Polish war cemetery in Monte Cassino was designed by architects: Edward Hryniewicz and Jerzy Skolimowski. At the entrance of this unique necropolis there is a monument with the inscription:

"For our freedom and yours, we, Polish soldiers, gave God the spirit, the body of Italy, and the heart to Poland" (Source: www.montecassino.org.pl )

In 1970, next to his soldiers, their commander, General Władysław Anders, was buried there, and on May 21, 2011, the ashes of his wife Renata Bogdańska were buried here. She accompanied the Corps from Buzuluk, through Totskoye, Iran, Iraq, and Palestine until the end of their struggle. She was the first to sing the song "Red Poppies at Monte Cassino" after the victorious battle.

The war cemetery at Monte Cassino (Source: Wikipedia)

At Monte Cassino there remained commanders, friends, a piece of his life, and a piece of Leonard Jędrzejczak's heart.

Translation from Polish by Andrew Woźniewicz.