Spider silk, known as babie lato (eng. equiv. Indian summer), wanders with the wind into the unknown, entwining plants, and shimmering in the sun. Scientists are studying their origins and properties; they inspire artists, and for walkers, they are a beautiful, fleeting symbol of the golden Polish autumn. This theme was most famously made famous by Józef Chełmoński, whose painting "Indian Summer" is in the collection of the National Museum in Warsaw.

For the Indian summer phenomenon to occur, the weather must be suitable. Ideally, the air temperature should be around 20 degrees Celsius, humidity should be maintained at 30-40 percent, and wind speeds should not exceed 3 m/s. In Poland, this situation usually occurs around the Fall equinox (September 21st). Thermal contrasts on Earth between midday and midnight are small at this time. Spiders of various families sense these parameters using sensory setae on their bodies and begin to weave threads, which the wind will carry them on, allowing them to find a suitable winter habitat, search for food, and colonize new areas. Spider "autumn travelers" belong to several families, including the Arachnidae, Araneidae, and Omatidae, which include many species of these insects.

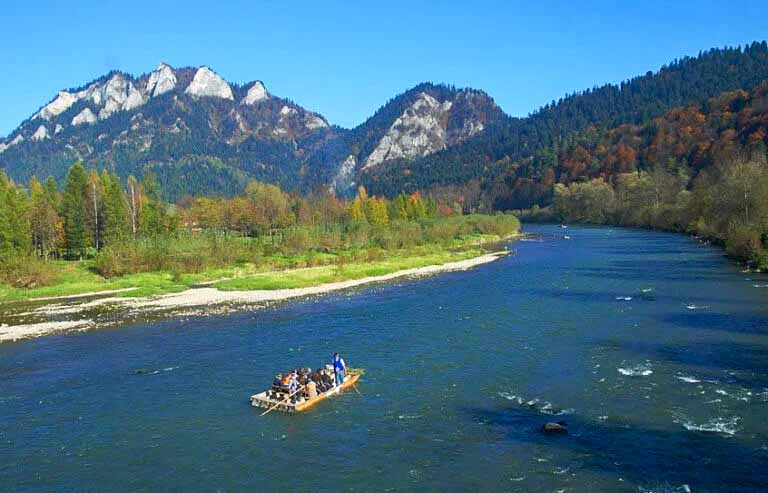

Indian Summer (Source: Unsplash/mohamed-b)

They can soar to altitudes of up to two thousand meters (6 thousand feet) and fly continuously for about a month without eating, for hundreds of kilometers. There's even a Polish proverb illustrating this natural phenomenon: "The Indian summer flies to races around Saint Jadwiga." This saint's commemoration falls on October 15th.

The structure of gossamer threads is also impressive. They are composed of two proteins: fibroin and sericin, which are also components of silk thread. Although thinner than human hair, they are incredibly strong yet flexible, water-insoluble, and non-allergenic. They could be used in medicine, for example, to make surgical threads, or in the clothing industry.

Inspiration for Literature

Hanna Zdzitowiecka, a writer, poet, and radio playwright, tried to explain to young children in the mid-20th century how spiders fly without wings. She also had a pre-war diploma in agricultural engineering, so in her short story "Spider Planes," she delivered her lecture not only with grace but also with professionalism. She included the story in the collection "From Spring to Spring," published in 1959 with her co-author Stefania Szumowa, also a children's writer and a graduate of nature studies courses.

The mysterious Indian Summer was in keeping with the melancholic poetics of Young Poland. In his poem "Indian Summer," Leopold Staff compared the thin, silver threads of spiderweb drifting in the air to fleeting dreams, night visions, and hopes. Henryk Zbierzchowski, a poet of Staff's generation and also a native of Lviv, known as the bard of the city, in a poem dedicated to Indian Summer, admired the lightness, transience, and elusiveness of the "golden and spiderweb filaments" floating over the fields. Only slightly older than both of these poets, another poet, Zenon Przesmycki, saw Indian Summer as a sign of a turning point in nature, a moment of transition from summer to autumn, warmth to cold, and even life to death.

"Indian Summer" – a painting by Józef Chełmoński (Source: DlaPolonii.pl)

A Painterly Monument to Indian Summer

In Polish culture, however, the greatest "monument" to the Indian Summer was erected not by a writer, but by a painter. Józef Chełmoński's "Indian Summer" is a painting belonging to a group of iconic works of national art. It was created exactly one hundred and fifty years ago, in 1875, after the painter's return from Ukraine, in his Warsaw studio located in the Hotel Europejski.

It's not easy to find the subject in the painting. The viewer's attention is most drawn to the single dynamically captured fragment – the raised hand of a shepherdess lying on the ground. She makes a gesture, and the eye follows. The heroine catches gossamer strands. She plays with them while taking a break from hard work in the field. Cows graze in the distance. A black dog watches over the gathering. The sky is heavy and overcast, the earth gray-green. Yet the scene seems idyllic. The long gossamer strands, lingering above the girl, distract her thoughts from her duties and usher in a different, blissful reality.

This painting, by Chełmoński, then only twenty-six years old, was exhibited by the prestigious Society for the Encouragement of Fine Arts and caused a scandal not only in Warsaw's salons. The artist was accused of trivializing the subject matter and of indecency, for depicting a peasant woman with dirty feet. A reviewer in the then-current "Gazeta Polska" wrote: "a pale, powerless, and colorless painting."

It took years for the excitement to subside and for critics and audiences to recognize Chełmoński's "Indian Summer" as a masterpiece. The Germans looted the painting during World War II. It was discovered, along with many other masterpieces, at Fischhorn Castle in Austria in 1945, and returned to Poland the following spring.

Where does the name of this phenomenon come from?

Not only are the scientific origins of the Indian summer phenomenon and its cultural presence interesting, but also the origins of its name. Its origins may lie in several sources, as discussed by scholars of the Polish language and our traditions: Samuel Bogumił Linde, Aleksander Brückner, Zygmunt Gloger, and Władysław Kopaliński.

The first element of the Polish name (babie, pertaining to an old woman) may evoke an elderly woman. "babie lato" would therefore refer to the late stage of this season, and the silver spiderweb threads would evoke the elderly woman's long, gray hair. In this interpretation, "babie lato" would signify late summer, the twilight of this season.

Zygmunt Gloger, in turn, linked the strands of gossamer to "yarn from the spindle of the Virgin Mary." Mary was also immortalized in the role of a woman at work, caring for the home and full of concern for her loved ones. Therefore, according to the apocryphal texts, she was said to have eagerly sat at the spinning wheel. Gossamer would thus be yarn from Mary, passed down to the earthly realm for housewives, so that they would remember to prepare winter clothing for their children and needy orphans.

Indian summer occurs all over the globe, so in our country we often encounter spiders belonging to species native to very distant lands. Nature has thus provided the entire world with this magnificent spectacle of the tiny insects' aerial journeys. Even people who dislike or are even afraid of spiders respond with sympathy to their delicate "planes." Many Poles observe them and experience their charm in a special way. Without colorful leaves, handfuls of chestnuts, abundantly fruiting orchards, baskets full of mushrooms, and the threads of Indian summer, it's difficult to imagine a golden Polish autumn.

Translation from Polish by Andrew Wozniewicz.